But a few weeks ago on Twitter, Dr DeBoer made some unfortunately uninformed remarks regarding the remuneration of physicians in the United States. Let me transcribe a series of tweets he published:

I'm on board with breaking the doctor cartel......Because their professional association artificially restricts the number of people who can become doctors.....The American Medical Association uses its massive lobbying and professional power to artificially restrict doctor licensure.....This in turn leads to the objectively, indisputable fact that American doctors are massively overpaid.....These sky-high salaries, compared to countries with better health outcomes, in turn make US medicine hideously expensive.

You can make a great summer salad by peeling all your apples and oranges and mixing the slices all together but it's not a great way to spin an argument. Dr DeBoer is aghast that American doctors are more generously reimbursed than their European colleagues. Would he be troubled to know that American college professors are paid more than they are in Europe? Or that nurses average $70k in the United States and $44k in the UK? That the ratio between American CEO to average worker pay is two to three times higher than what it is in European nations? That car mechanics make 30-50% more in the USA vs Europe? It's amazing: the wealthiest nation on earth tends to pay its citizens commensurately more for services rendered.

The United States, additionally, is a more expensive place to live. And although American physicians make more in terms of absolute salary and income, reimbursements have been falling over the past several decades, relative to inflation. As per the paper from Tu and Ginsburg:

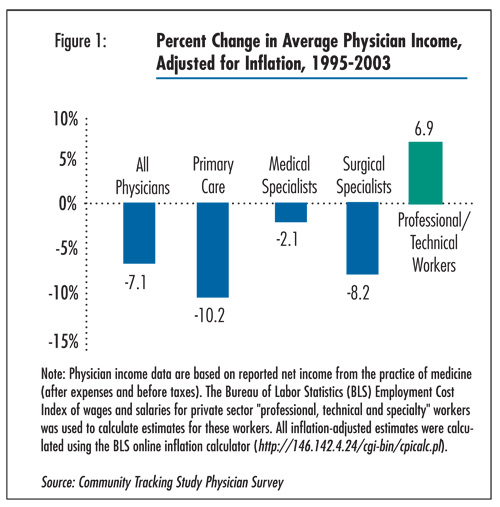

Between 1995 and 2003, average physician net income from the practice of medicine declined about 7 percent after adjusting for inflation, according to HSC’s nationally representative 2004-05 Community Tracking Study Physician Survey (see Figure 1and Data Source). Primary care physicians and surgeons fared the worst in keeping pace with inflation, while medical specialists fared the best.

When examining American doctors incomes as a ratio of earnings to GDP per capita, physicians make about 5.8 times what the average American worker earns. This ratio is commensurate with physician pay in Germany, Canada, France, and Australia. Furthermore, if one were to break it down even further and compare American doctors with other "high earners" (i.e. those with incomes in the 95-99th percentile) one finds that American specialists make 37% more than other high earners---which is less than what non-American specialists make compared with high earners in European countries (45%). General practitioners in the United States, on the other hand, actually make only about 90% of what a high income family earns. this number holds steady when compared with non-American OECD nations.

In essence, when corrected for overall national wealth and GDP, American doctors aren't all that different from their European colleagues. The Cutler paper goes on to say that other factors are more contributory to explosive American health care costs--- things like wasteful administration costs, the overall intensity of treatment and overuse of unnecessary resources, the relative higher costs of drugs and medical devices, etc.

Uwe Reinhardt, the eminent Princeton economist, has written that American doctors are not the problem when it comes to spiraling healthcare costs:

Cutting doctors’ take-home pay would not really solve the American cost crisis. The total amount Americans pay their physicians collectively represents only about 20 percent of total national health spending. Of this total, close to half is absorbed by the physicians’ practice expenses, including malpractice premiums, but excluding the amortization of college and medical-school debt.

This makes the physicians’ collective take-home pay only about 10 percent of total national health spending. If we somehow managed to cut that take-home pay by, say, 20 percent, we would reduce total national health spending by only 2 percent, in return for a wholly demoralized medical profession to which we so often look to save our lives. It strikes me as a poor strategy.

I hate to be in a position where I am groveling before the public to justify my income. As a general surgeon, I work long unpredictable hours, I deal with ungodly stress and strain, I'm tired all the time, I miss out on a lot of the things I enjoy. But I can't imagine doing anything else. I know what I do has value. This is the life I have chosen. And i knew that going into it. I make more than the average Joe, this is true. I don't want to say I "deserve to" because then you fall down the slippery slope of subjective assessments of who deserves what and how much--- doesn't a good elementary school teacher "deserve" a lot more or an inner city Big Brothers Big Sisters coordinator? etc etc--- but I certainly don't deserve to be smugly admonished as representative of the primary cause of our exploding healthcare cost crisis by a thinly informed intellectual from Purdue.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed