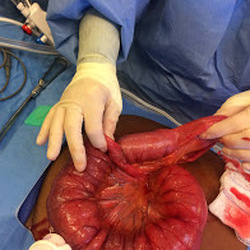

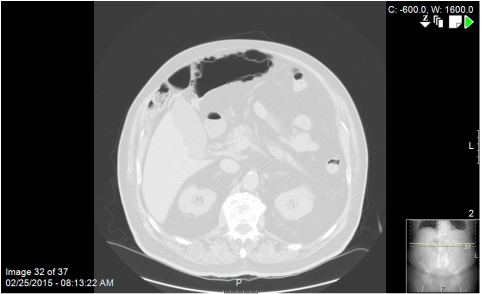

Although the guy had a relatively benign abdominal exam, I took him to the OR for laparoscopic exploration based on CT findings. His sigmoid colon snaked behind his floppy cecum and twisted like licorice as the decompressed proximal and distal limbs curved around the hepatic flexure and came to a cul de sac behind the transverse mesocolon. It took a little work identifying the ends and reducing the dilated loop but I was ultimately able to get the entire redundant sigmoid into the wound. The dilated terminus of the loop had obvious, visible pneumatosis in the muscular wall, as if someone had inserted bubble wrap just under the serosa. It was very weird to palpate. Strangely, the bowel looked entirely viable. No ischemic change. Nothing to suggest vascular compromise. Somehow, though, despite the chronic volvulus, he had been able to have bowel movements and avoid a complete colonic obstruction. I ended up performing a sigmoid resection to eliminate some of the redundancy and prevent future occurrences. He did well. When I first saw him I was fairly unimpressed; soft, non tender belly. But the radiologist talked me into it.

|

This was an older guy who presented with mild, vague upper abdominal symptoms and the above CT scan. What you should note is the air-density structure located anterior and to the left of the liver that, believe it or not, is a long redundant loop of sigmoid colon that had meandered behind a laxly fixated cecum, up the right paracolic space and behind a band of omentum above the transverse colon. The pneumatosis is obvious on the above lung windows.

Although the guy had a relatively benign abdominal exam, I took him to the OR for laparoscopic exploration based on CT findings. His sigmoid colon snaked behind his floppy cecum and twisted like licorice as the decompressed proximal and distal limbs curved around the hepatic flexure and came to a cul de sac behind the transverse mesocolon. It took a little work identifying the ends and reducing the dilated loop but I was ultimately able to get the entire redundant sigmoid into the wound. The dilated terminus of the loop had obvious, visible pneumatosis in the muscular wall, as if someone had inserted bubble wrap just under the serosa. It was very weird to palpate. Strangely, the bowel looked entirely viable. No ischemic change. Nothing to suggest vascular compromise. Somehow, though, despite the chronic volvulus, he had been able to have bowel movements and avoid a complete colonic obstruction. I ended up performing a sigmoid resection to eliminate some of the redundancy and prevent future occurrences. He did well. When I first saw him I was fairly unimpressed; soft, non tender belly. But the radiologist talked me into it.

1 Comment

Today in the NY Times there is an article questioning the utility of the 30 day mortality as a valid quality metric in cardiac surgery. In some states, hospitals are required by law to publicly report 30 day mortality rates after cardiac procedures like valve replacement and coronary bypass grafting. The article presents a case study wherein a 94 year old patient underwent aortic valve replacement and, unsurprisingly, suffers multiple post operative setbacks and complications. Ultimately, discussions of palliative care and withdrawal of aggressive support were delayed until she reached the magical 30 day milestone. On day 31, she was made DNR and expired shortly thereafter.

The article makes valid critical points about the arbitrary nature of "30 day mortality rates". Specifically, that surgeons may be reluctant to pursue aggressive care in certain patients for fear of hurting their "stats". In addition, there is a real concern that palliative/hospice care may be delayed even when it becomes obvious that the situation is futile, thereby subjecting the patient to weeks of unnecessary suffering hooked up to ventilators in an ICU. These are good points. But the lede has been buried. The real question ought to be: "Why the hell would you perform aortic valve replacement on a 94 year old patient?" Simply choose to not put such a patient on the operating table and you don't have to worry about keeping her alive for 30 days. And if surgeons feel increasingly dissuaded from performing high risk surgery on poor surgical candidates, then so be it. Maybe that wouldn't be such a bad thing. I like the idea of total transparency in surgery. I like published mortality rates. I like the idea of comparing hospitals using hard cold data. And I think Americans ought to have a right to access information that may impact decision making in terms of where an operation is performed. This ought not to be all that controversial.... One of the obligations of a medical or surgical specialist is to communicate with the referring primary care provider. This can take many forms--- a phone call, texting via smart phone, email, messages sent via EMR, and dictated letters. The format is pretty standard no matter what medium is chosen. You thank the referring doc for the consult request, you give some brief background info about the patient in question, and then you articulate an assessment and plan. Then you thank the doc again. Multiple times if necessary. Because your livelihood depends on whether or not that doctor decides to continue to send patients your way.

My practice is to freely text physicians I know well about their patients. It's instantaneous, it's informal, it breeds a certain collegial connectivity that is good for business. I also like free-form written emails via our internal encrypted system. In addition, our outpatient EMR auto-creates "referral letters" to primary doctors. These get sent to the doctor's inbox as soon as I click "sign" on my office notes. These notes are really something. Not exactly an unearthed archive of F Scott Fitzgerald corresponding with Hemingway, these babies. Some computer algorithm takes your office note, chops it up into relevant blocks of transferable data and information, splices in seemingly human-sounding phrases and sentences, and then synthesizes it all back together to make it look like an actual letter. I sometimes try to type in a block of text toward the end in an attempt to personalize things but that usually just gets buried under an avalanche of x ray reports, review of system minutiae, exam findings, and various instances of tortured computer-generated syntax. Prior to EMR and texting and instantaneous communication, most specialists had no other option but to dictate referral letters to their feeders. And for some reason it evolved that the referral letter had to be composed in this faux-formalized, knock-off Henry Jamesian diction and syntax, as if American doctors were a bunch of 18th century courtiers. Ezekiel Emanuel's group has a paper in JAMA Oncology this month that seeks to assess the role "demanding patients" have on overall health care costs in oncology. They conclude as follows: Patient demands occur in 8.7% of patient-clinician encounters in the outpatient oncology setting. Clinicians deem most demands or requests as clinically appropriate. Clinically inappropriate demands occur in 1% of encounters, and clinicians comply with very few. At least in oncology, “demanding patients” seem infrequent and may not account for a significant proportion of costs. Well that's all good and well. I don't necessarily agree with the conflation of "demand" with "request"--- to wit, a cancer patient asking for an adjustment in dosage of pain medications ought not to be equated with a patient who insists upon an MRI for low back pain. But whatever. I don't disagree with the results. In my own clinical practice I cannot remember an incident where I was forced to order some expensive test because an overly Google-ized patient demanded it. My problem with this paper is the underlying premise. The opening sentence of the abstract is: Surveyed physicians tend to place responsibility for high medical costs more on “demanding patients” than themselves. Who, I wonder, are these "surveyed physicians"? Is there a citation in the bibliography to support such a claim? Of course not. Who exactly are all these physicians who are blaming patients for the healthcare cost spiral? Why is it taken as indisputable, unassailable knowledge that doctors attribute health care costs to patient demands? And yet, this "fact" serves as the premise of the entire project. And the Emanuel group dutifully goes about proving that, no, patient demands do not significantly impact either physician decision making or the number of tests ordered. They have demonstrated the invalidity of a claim that no one is making anyway. At least not by doctors. I guess that counts as research these days.

The reality is that this is propaganda. Physicians are greedy. They will do anything to preserve fee-for-service models. They blame others for healthcare costs. They blame patients for the tests they order. See? This study has proven it..... I woke up refreshed this morning. I was asleep by 8pm last night. Sweet, uninterrupted, restorative sleep ensued. I staggered home from a busy Friday-- six scheduled cases, rounds, etc---- fell into bed in a hollowed out heap of exhaustion. The night before I had received the dreaded midnight phone call from the ICU about a patient with a CT showing massive pneumoperitoneum. I spent the next 7 hours caring for him. Then a shower and a mainline infusion of coffee and straight to another hospital for the scheduled surgeries. I'm not as young as I used to be. All-nighters aren't glancing blows for me anymore; I feel it in every fiber of my being.

The patient was older, but not that old. I mean, I hear that someone is 85 or more, give or take, and I immediately start thinking of ways to hide the scalpels and clamps. Chronologically speaking, he wasn't too bad but he carried a lot of miles on those years. Advanced stage cancer, severe pulmonary co-morbidities, multiple hospitalizations over past few months. I asked the nurse, is the family there? Yes, a son and a daughter. The son went downstairs for coffee. Ok, I said. I'll be in. The guy was already intubated and they had just started levophed to maintain a pressure. First thing I notice are areas of mottling on his shins and flanks. Nothing more ominous in my experience. His abdomen was distended tight like he'd swallowed a beach ball. He seemed to wince when I percussed him. He opened his eyes and I saw fear. Post Update Below

I talked about this last week. Vox is running a year long series on "fatal medical errors". Last week I exposed some of the incoherent, misleading aspects in Sarah Kliff's opening salvo. Today I need to spend some time addressing foundational reference points of her entire project, namely the idea that hundreds of thousands of Americans are dying due to physician incompetence. She cites two papers to support this. I am a very boring, uninteresting person without many hobbies or likes. I printed off those papers and gave them a close read this week. In 1999 the Institute of Medicine published a study called "To Err is Human" that claimed 100,000 people were dying every year from health care system malfeasance. The authors used data retrospectively gleaned from patient charts from several New York hospitals from the year 1984. I found the paper to be a little stingy with the details. (What defines an "adverse event"? To what extent are adverse events the result of physician negligence? Who decides?) Plus it was based on data and medical practice paradigms from 30 years ago. All gallbladders were getting whacked out via giant RUQ saber slash incisions 30 years ago. I don't even know if penicillin had been discovered in 1984. I think kids were still being hooked up to Iron Lungs for polio back then. The 2nd paper Ms. Kliff cites to fan the flames of outrage is one from the Journal of Patient Safety in 2013. Now that's more like it. Just 2 years ago. I sunk my teeth into that one. This is the paper that unabashedly alleges that potentially (we'll get back to this potentiality later) 400,000 people are getting cut down every year by doctors afflicted with hands of death and destruction (HODAD syndrome). This one had my attention. JACS this month has a solid study from Japan on the use of diverting stomas in the setting of rectal cancer. This was a prospective, multicenter cohort study of 936 patients who underwent low anterior resection (LAR) for rectal tumors within 10 cm of the anal verge. The results were as follows: ...overall rate of symptomatic AL was 13.2% (52 of 394) in patients with DS vs 12.7% (69 of 542) in cases without DS (p = 0.84). Symptomatic AL requiring re-laparotomy occurred in 4.7% (44 of 936) of all patients, occurring in 1.0% (4 of 394) of patients with DS vs 7.4% (40 of 542) of patients without DS (p < 0.001). After PSM, the 2 groups were nearly balanced, and the incidence rates of symptomatic AL in patients with and without DS were 10.9% and 15.8% (p = 0.26). The incidences of AL requiring re-laparotomy in patients with and without DS were 0.6% and 9.1% (p < 0.001) This suggests that diverting ostomy (either a loop ileostomy or transverse colostomy) constructed during a LAR for lower rectal tumors can attenuate the deleterious effects of anastomotic leaks. Which makes complete sense. Leaks happen in gastrointestinal surgery. This is a vexing, unspoken problem for surgeons who perform a lot of bowel surgery. Did you know that, depending on the literature cited, leaks can complicate anywhere from 3%-28% of anastomoses? That's a lot of leaks! And the consequences of a leak, especially pelvic colorectal connections, can be devastating. The idea behind a diverting stoma is to protect an immature, potentially compromised anastomosis. Patients with rectal cancer are often treated with neoadjuvant chemo-radiation (not specified in the paper above) and that distal rectal stump used in the anastomosis is not always the best hunk of flesh to work with. Small leaks, which, unprotected, can lead to rapid pelvic sepsis and eventual complete anastomotic dehiscence, can be mitigated by proximal diversion. Instead of stool pumping out through a micro-perforation, a small leak can, with time and re-direction of fecal flow, be allowed to scar down and heal spontaneously.

I don't do a lot of low rectal cancer resections but I find the diverting ileostomy to be an extremely useful tool in my armamentarium in the setting of severe perforated diverticulitis. A lot of these patients need urgent or semi-urgent operative intervention after failure of conservative management. A bowel prep is usually contra-indicated. The pelvis is contaminated. The surrounding tissues are often edematous and friable. In the old days, everyone got a Hartmann's procedure (end colostomy and Hartmann's rectal pouch left in the pelvis. But we found over the years that reversing a Hartmann's colostomy was frought with morbidity. Leaks could occur. Surrounding structures could be injured. And sometimes the post peritonitis scarring resulted in a frozen, socked in pelvis with marginally identifiable anatomy. As a matter of fact, for a variety of reasons, only about 70-75% of Hartmann's colostomies ever get reversed. My practice is to make liberal use of the loop ileostomy if I have any concern about my pelvic colorectal anastomosis. This allows the new conduit to heal without the stress of fecal matter flowing through it. A barium enema is ordered after 6 weeks or so to confirm healing and the patient is brought back to the OR for a pretty straight forward, far less stress-inducing loop ileostomy reversal. There is an interesting paper from JAMA Surgery this month (on-line version only as of yet) that studies the use of NSAID's (non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) in the post operative period and their impact on anastomotic leak rates. NSAID's are medicines like Alleve and Motrin. As a surgeon, I prescribe Motrin to most of my post op hernia and laparoscopy patients for non-narcotic pain control. I am also a big fan of the intravenously administered NSAID, Toradol. Toradol is an extremely useful adjunct in the management of post operative pain in the inpatient setting. I order it often. (Also, NFL football players seem to like it, not always to their benefit.) The risk with Toradol and other NSAID's in the post op period was usually related to kidney injury and potential bleeding complications. But NSAID's work by attenuating the body's natural inflammatory response to stress. And sometimes that inflammatory response is beneficial. As a surgeon I need that inflammatory response to occur, especially if I am sewing one end of bowel to another. Those inflammatory mediators bring the kinds of cells and proteins necessary for a strong anastomosis. The JAMA paper is a large retrospective cohort study over over 13,000 patients who had undergone colorectal or bariatric surgery at over 40 hospitals in Washington state. The question the investigators asked was: how was the leak rate affected when NSAID's were started within 24 hours of surgery? The findings: The overall 90-day rate of anastomotic leaks was 4.3% for all patients (151 patients [4.8%] in the NSAID group and 417 patients [4.2%] in the non-NSAID group; P = .16). After risk adjustment, NSAIDs were associated with a 24% increased risk for anastomotic leak (odds ratio, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.01-1.56]; P = .04). This association was isolated to nonelective colorectal surgery, for which the leak rate was 12.3% in the NSAID group and 8.3% in the non-NSAID group That's a significant finding! The good news is that the statistical differences were only seen in patients undergoing non-elective colon surgery. These are typically semi-urgent cases in a patient population already compromised by factors of infection or malignancy. NSAID's, given their mechanism of action, could very well function as a tipping point that compromises anastomotic healing in such cases. Further study is certainly warranted, but I'm inclined to change my practice. The next perforated diverticulitis case I get that can be treated with a single stage sigmoid colectomy will probably just get a PCA post op.

Sarah Kliff from Vox is up to some interesting shenanigans. Last week she published an interesting post entitled "Medical errors in America kill more people than AIDS and drug overdoses". This would have been a fearful headline in, say, 1985. But, in the year 2014, with the advent of combination anti-retroviral therapy, where HIV positive Americans live, on average, 40-60 years after initial diagnosis, it is unclear what point Ms. Kliff is trying to convey. Irony? What she is struggling to communicate is a reference to an Institute of Medicine (IOM) study from 1999 that made the claim that 98,000 Americans (often rounded to an even 100,000) are KILLED every year by medical errors. This study was based on retrospective data, subsequently used for predictive purposes, from 1984. (Hence the AIDS reference in Kliff's article). That's a long time ago, right? We need to delve deeper into the data on that IOM report on a subsequent post. In any event, Ms Kliff has composed a structurally awkward post parceled into seven numbered sections. Section 2 is titled: "Bed sores are huge source of harm in the health care system". Hey, I'm as anti-bedsores as anyone but I fail to see the relevance of bringing up bed sores in the the context of a piece ostensibly about patients dying from medical errors. Kliff begins the section discussing wrong site surgeries and transitions to : But they aren't what cause the most harm in American health care. It's the less stunning, more quotidian mistakes that are the biggest killers. Take, for example, bed sores. The construction of her sentences leads one to believe that "quotidian" mistakes, like BEDSORES, are the biggest killers. This should strike an average healthcare professional as ridiculously absurd. Bedsores demonstrably are not striking down thousands of patients every year, like an army of ghastly demons leeching onto unsuspecting patients' sacrums and heels and ischial tuberosities. And Ms Kliff seems to know this as well, as betrayed by this line: A 2006 government survey found that more than half a million Americans are hospitalized annually for bed sores that are the result of other care they have received. 58,000 of those patients die in the hospital during that admission. So yeah. Bedsores are found in frail, elderly, non-ambulatory, demented patients who present to hospitals with a host of medical problems. Many of them die. Many of them have incidental bedsores. Correlation is not causation, of course. Ms Kliff acknowledges this. And her unnamed "experts" sure are getting a lot of mileage out of the phrase "almost certainly" when asked to provide evidence of an association. This is obscurantism is its finest form.

After the bed sore non-sequitor, Kliff makes some valid points about physician transparency and the difficulty of identifying errors when they occur. She also assails the "fee for service" model as a source for disincentivization to correct mistakes and prevent them from happening again. Finally she assures her readers that this post is the first in a year long series investigating fatal medical errors. She then affixes a form for readers to fill out if they or their loved ones have been the victim of a medical error. This form asks "Type of Harm" (and the participant is to check all that apply). Choices include: "Infection", "Surgical Injury", "Bedsores", "Fall", "Medication error", "Blood Clot", "Device (ortho or cardiac). Ms Kliff has committed a very common error here, creating a false equivalence between the concept of known complications related to procedures or disease processes and true negligence/malpractice. Surgical injury, of course, is my personal favorite listing. I love the use of the pejorative word "injury" rather than "complication" or "unexpected outcome". So now surgical site infections, post op pneumonia, hernia recurrences, duct of Luschka leaks, anastomotic dehiscences, and other surgical complications are re-defined as "injuries" suffered as a result of "medical errors". Certainly many bad surgical outcomes are the result of incompetence or negligence. Most are not. Most are simply known complications of a well described procedure. Mixing up the two is tantamount to journalistic malpractice. It will be interesting to read Ms Kliff's follow up articles on this important topic.....  Tragic news from Boston a few weeks ago. Dr Michael Davidson, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women's Hospital was gunned down outside his clinic by a deranged family member of one of his former patients. Stephen Pasceri was a licensed gun owner, without a history of violence, who strode into Dr. Davidson's clinic, asked to speak to with him, and, upon Davidson's harried appearance (in the middle of a busy office hours) proceeded to assassinate him in broad daylight. Pasceri then ended his own life shortly thereafter. The backstory was that Dr. Davidson had recently cared for Pasceri's mother. There were complications after a procedure, she passed away. Pasceri would have probably articulated his psychotic break as an "act of retribution". Which is bullshit, of course. Several years prior to this heinous episode, he had drawn attention to himself after the death of his father regarding a bill for services rendered after his dad had been emergently transported to the hospital following a massive myocardial infarction. The old man had refused Medicare part B and the estate received a bill for 8 grand after the funeral. Recently, the non-profit Cleveland Clinic Foundation announced plans to close its community hospital affiliate in the near west side community of Lakewood. The closing will coincide with the opening of a new $220 million, 400, 000+ square foot combo hospital/outpatient health center in the city of Avon, further to the west. This comes on the heels of the closure of the Clinic's Huron Road Hospital in East Cleveland in 2011 and subsequent expansion of its main east side community hub, Hillcrest Hospital. Some relevant bullet points to consider:

This past December, Ohio became the 20th state to pass a law mandating that hospitals and clinics performing mammography screening to notify a patient in writing if results suggest something known as "dense breast tissue". Standard mammography creates a 2-D image of breast tissue. In general, this is sufficient for screening purposes. However, especially in younger patients, the presence of dense breast parenchyma can lead to higher false negative readings and more indeterminate results that may lead to higher rates of invasive biopsies.

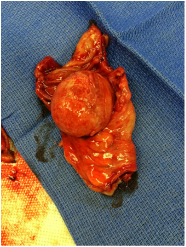

A newer imaging technology, called digital tomosynthesis, creates highly focused 3-D images of breast tissue. Initial research seems to suggest that this can improve both early detection rates of smaller cancers and eliminate the need for unnecessary biopsy procedures on clinically insignificant findings. The law passed in December is supposed to prompt patients to ask their respective health care providers about the need for follow up digital tomosynthesis. Several questions are begging to be asked: 1) Why don't we just screen everyone with 3D digital mammography? Well, it's an issue of cost, of course. For most women, standard 2D mammography is sufficient. The 3-D machines cost twice as much and some insurance companies will give patients a hard time about coverage. Most tertiary care centers and dedicated breast cancer facilities have the technology but universal availability is a problem. Rural and critical access hospitals simply cannot afford to invest in an expensive new technology that may only be intermittently indicated. In the long haul, as costs inevitable plateau and decrease, it is certain that 3-D digital mammography represents the future. But for now, we run the risk of creating tiered levels of care, depending on where one lives. 2) Why is this being handled by the state legislative bodies? Wouldn't it make more sense for medical decision making protocols to come from , like, oh, I don't know, trained healthcare professionals rather than laymen elected officials in Columbus? Wouldn't a consensus statement from, say, the American Society of Breast Surgeons or a similar entity, make more sense? Do we not have enough laws on the books? What would be the consequences of violations of such a law? Criminal prosecution, in addition to any tort liability? Doctors and hospital administrators cuffed and read their Miranda rights in the physician lounge? Will this set the precedent for future legislation guiding physician/patient communication paradigms? When I take out a patient's colon cancer, the expected standard of care surveillance recommendation would be for that patient to get another colonoscopy one year after surgery. What if I don't document that recommendation exactly as per state guidelines? What if the patient is either non compliant or never received the written notification because of a change in address? Am I criminally liable? It all just strikes me as unnecessary and absurd. It ought to be enough to expect doctors and healthcare providers to be professionally responsible and to fulfill basic standard of care requirements. Deviations from these standards put one at risk of malpractice litigation. There's enough negative reinforcement in that threat alone.....  Intussusception of jejunum just prior to manual reduction Intussusception of jejunum just prior to manual reduction I saw a lady in the ER presenting with abdominal pain, nausea, progressive anorexia for about 6 weeks. A CT scan suggestive high grade obstruction with intussusception of the small bowel. Now we don't see something like this everyday. Intussusception occurs when the proximal bowel sort of telescopes itself into the more distal bowel lumen, leading to congestion, obstruction, and, in some cases, ischemia of the involved segments. Intussusception in an adult always raises concerns for underlying malignancy. Intra-lumenal masses or tumors can act as a lead point wherein, via peristalsis, the more proximal bowel can "grab hold" and intussuscept. Fortunately, this patient had a benign submucosal fibroid tumor that led to her intussusception. We resented the segment of bowel harboring the mass and she went home a happy camper in a couple of days. Many times, intussusception is the initial presentation of a more sinister process, like lymphoma, or carcinoid tumors, or invasive adenocarcinomas. The concept of "patient satisfaction" has assumed a prominent perch in American healthcare delivery. Somehow, this vague, nebulous metric has been indiscriminately tied into the way we reimburse hospitals and physicians. In fact, patient satisfaction can represent up to 30 % of a hospital's score in the federal value-based purchasing system, which can greatly affect Medicare payments (by as much as 1%).

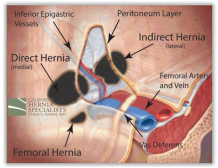

Controversy has arisen, however, regarding the validity of "patient satisfaction" as a useful yardstick. Two articles from the literature illustrating this recently caught my eye. JAMA Surgery in April 2013 published a much cited article that evaluated the relationship between patient satisfaction scores and hospital compliance with Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) metrics. Interestingly, in a study of 31 hospitals, patient satisfaction was found to be independent of the extent to which hospitals followed standard guidelines to help reduce post operative infectious complications. A couple of months ago, Annals of Surgery studied 171 hospitals over 11 years, looking for a correlation between patient satisfaction and surgical outcomes. The findings of the study certainly raised some eyebrows. The only surgical outcome indicator associated with high patient satisfaction scores was a low mortality rate. (Let us hope that no one is surprised by this particularity.) More confounding was that complications and higher readmission rates after surgery had no statistical effect on a patient's reported satisfaction experience. The only variables associated with high satisfaction scores, other than low mortality, were larger hospitals (in square footage, I guess) and hospitals with a high surgical volume. These papers highlight the concern many of us in the trenches have with using subjective, highly capricious metrics like HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores as a reliable measure of quality. You end up in an upside down world where patients with horrible surgical complications effusively praise their doctors and nurses for being so "compassionate and caring during a difficult time" and, on the other hand, where patients who sail through difficult major colon resections give a hospital a bad score because their TV only had three working channels and the newspaper delivery volunteer was rude every morning. Quality is a metric that cannot be measured via proxies. We need to start being more honest about it. Using HCAHPS and patient satisfaction scores is just a fancy way of equivocating on transparency. We have a perfectly fine, already available method of measuring quality: simply open up the drapes and let some light into the world of surgical outcomes. If you want to let the public know how well a hospital or surgeon is performing, don't think you are providing a valid answer by instead publishing bullshit like "patient satisfaction is very high!". Publish the actual outcomes. If a hospital performs 1,000 hernia repairs every year, then maybe the public has a right to know recurrence rates, infectious complications, mortality rates, etc. Same thing with abdominal procedures and orthopedic interventions. We have been doing the exact same thing in the realm of cardiothoracic surgery for years. Open up the books. May the best man win.  Inguinal hernia represents one of the more common indications for referral to a general surgeon. Patients who come see me describe a variety of symptoms ranging from "slight groin bulge when I cough" to "a dull ache" to "weird burning sensation" to "severe pain with activity". Hernias that are causing symptoms significant enough to incite a patient to seek an opinion from a physician (especially an older male who hates going to the doc, in general) probably ought to be repaired sooner rather than later. Not many surgeons would debate such a management protocol. The more controversial clinical scenario is the mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic inguinal hernia. Previous surgical literature has suggested that a conservative apporach of "watchful waiting" is appropriate. If symptoms worsen, then surgical intervention would be the next step. A new article from Annals of Surgery, however, suggests that, in select circumstances, even patients with minimally symptomatic or aymptomatic inguinal hernias ought to at least consider elective repair. This accords with an earlier study from the UK that found a benefit to earlier repair in patients without incapacitating symptoms. The driving rationale for this new recommendation is that 70-75% of men with initially asymptomatic hernias in the long term studies eventually developed symptoms (pain, most prominently) and elected to undergo surgical repair within 7-8 years. MY TAKE: I have several guiding principles when it comes to minimally symptomatic groin hernias.

|

AuthorJeffrey C. Parks MD, FACS Archives

February 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed